| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Many species use their body shape and coloration to avoid being detected by predators. The crab spider has the coloration and body shape of a flower petal which makes it very hard to see when stationary against a background of real a real flower ( [link] a ). In another example, the chameleon can change its color to match its surroundings ( [link] b ). Both of these are examples of camouflage , or avoiding detection by blending in with the background.

Some species use coloration as a way of warning predators that they are not good to eat. For example, the cinnabar moth caterpillar, the fire-bellied toad, and many species of beetle have bright colors that warn of a foul taste, the presence of toxic chemical, and/or the ability to sting or bite, respectively. Predators that ignore this coloration and eat the organisms will experience their unpleasant taste or presence of toxic chemicals and learn not to eat them in the future. This type of defensive mechanism is called aposematic coloration , or warning coloration ( [link] ).

While some predators learn to avoid eating certain potential prey because of their coloration, other species have evolved mechanisms to mimic this coloration to avoid being eaten, even though they themselves may not be unpleasant to eat or contain toxic chemicals. In Batesian mimicry , a harmless species imitates the warning coloration of a harmful one. Assuming they share the same predators, this coloration then protects the harmless ones, even though they do not have the same level of physical or chemical defenses against predation as the organism they mimic. Many insect species mimic the coloration of wasps or bees, which are stinging, venomous insects, thereby discouraging predation ( [link] ).

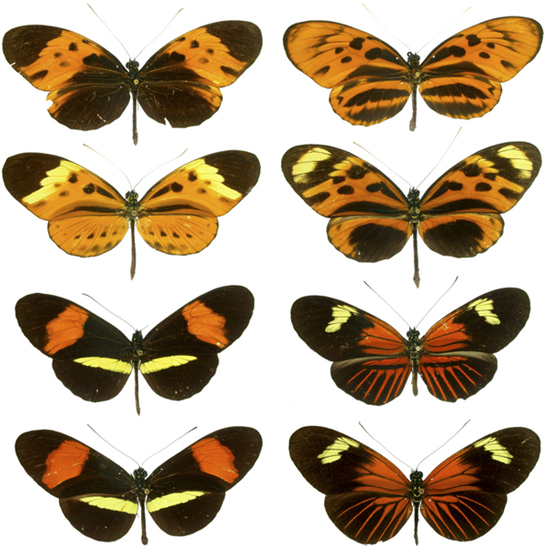

In Müllerian mimicry, multiple species share the same warning coloration, but all of them actually have defenses. [link] shows a variety of foul-tasting butterflies with similar coloration.

Resources are often limited within a habitat and multiple species may compete to obtain them. All species have an ecological niche in the ecosystem, which describes how they acquire the resources they need and how they interact with other species in the community. So, the plants in a garden are competing with each other for soil nutrients, and water. This competition between the different species is called interspecific competition. The overall effect on both species is negative because either one of the species would do better if the other species is not present. So, how do species reduce the overall negative effects of direct competition?

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?