| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Some of the most spectacular advances in science have been made in modern physics. Many of the laws of classical physics have been modified or rejected, and revolutionary changes in technology, society, and our view of the universe have resulted. Like science fiction, modern physics is filled with fascinating objects beyond our normal experiences, but it has the advantage over science fiction of being very real. Why, then, is the majority of this text devoted to topics of classical physics? There are two main reasons: Classical physics gives an extremely accurate description of the universe under a wide range of everyday circumstances, and knowledge of classical physics is necessary to understand modern physics.

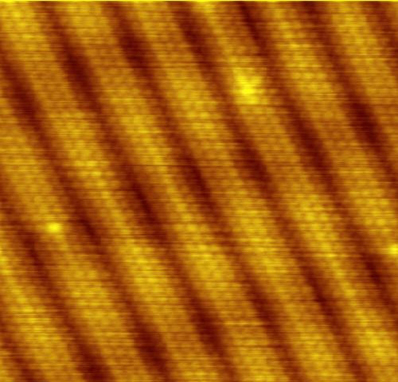

Modern physics itself consists of the two revolutionary theories, relativity and quantum mechanics. These theories deal with the very fast and the very small, respectively. Relativity must be used whenever an object is traveling at greater than about 1% of the speed of light or experiences a strong gravitational field such as that near the Sun. Quantum mechanics must be used for objects smaller than can be seen with a microscope. The combination of these two theories is relativistic quantum mechanics, and it describes the behavior of small objects traveling at high speeds or experiencing a strong gravitational field. Relativistic quantum mechanics is the best universally applicable theory we have. Because of its mathematical complexity, it is used only when necessary, and the other theories are used whenever they will produce sufficiently accurate results. We will find, however, that we can do a great deal of modern physics with the algebra and trigonometry used in this text.

A friend tells you he has learned about a new law of nature. What can you know about the information even before your friend describes the law? How would the information be different if your friend told you he had learned about a scientific theory rather than a law?

Without knowing the details of the law, you can still infer that the information your friend has learned conforms to the requirements of all laws of nature: it will be a concise description of the universe around us; a statement of the underlying rules that all natural processes follow. If the information had been a theory, you would be able to infer that the information will be a large-scale, broadly applicable generalization.

Learn about graphing polynomials. The shape of the curve changes as the constants are adjusted. View the curves for the individual terms (e.g. ) to see how they add to generate the polynomial curve.

Models are particularly useful in relativity and quantum mechanics, where conditions are outside those normally encountered by humans. What is a model?

How does a model differ from a theory?

If two different theories describe experimental observations equally well, can one be said to be more valid than the other (assuming both use accepted rules of logic)?

What determines the validity of a theory?

Certain criteria must be satisfied if a measurement or observation is to be believed. Will the criteria necessarily be as strict for an expected result as for an unexpected result?

Can the validity of a model be limited, or must it be universally valid? How does this compare to the required validity of a theory or a law?

Classical physics is a good approximation to modern physics under certain circumstances. What are they?

When is it necessary to use relativistic quantum mechanics?

Can classical physics be used to accurately describe a satellite moving at a speed of 7500 m/s? Explain why or why not.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics' conversation and receive update notifications?