| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Solution for (a)

The rotational kinetic energy is

We must convert the angular velocity to radians per second and calculate the moment of inertia before we can find . The angular velocity is

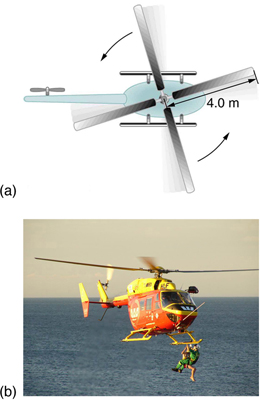

The moment of inertia of one blade will be that of a thin rod rotated about its end, found in [link] . The total is four times this moment of inertia, because there are four blades. Thus,

Entering and into the expression for rotational kinetic energy gives

Solution for (b)

Translational kinetic energy was defined in Uniform Circular Motion and Gravitation . Entering the given values of mass and velocity, we obtain

To compare kinetic energies, we take the ratio of translational kinetic energy to rotational kinetic energy. This ratio is

Solution for (c)

At the maximum height, all rotational kinetic energy will have been converted to gravitational energy. To find this height, we equate those two energies:

or

We now solve for and substitute known values into the resulting equation

Discussion

The ratio of translational energy to rotational kinetic energy is only 0.380. This ratio tells us that most of the kinetic energy of the helicopter is in its spinning blades—something you probably would not suspect. The 53.7 m height to which the helicopter could be raised with the rotational kinetic energy is also impressive, again emphasizing the amount of rotational kinetic energy in the blades.

Conservation of energy includes rotational motion, because rotational kinetic energy is another form of . Uniform Circular Motion and Gravitation has a detailed treatment of conservation of energy.

One of the quality controls in a tomato soup factory consists of rolling filled cans down a ramp. If they roll too fast, the soup is too thin. Why should cans of identical size and mass roll down an incline at different rates? And why should the thickest soup roll the slowest?

The easiest way to answer these questions is to consider energy. Suppose each can starts down the ramp from rest. Each can starting from rest means each starts with the same gravitational potential energy , which is converted entirely to , provided each rolls without slipping. , however, can take the form of or , and total is the sum of the two. If a can rolls down a ramp, it puts part of its energy into rotation, leaving less for translation. Thus, the can goes slower than it would if it slid down. Furthermore, the thin soup does not rotate, whereas the thick soup does, because it sticks to the can. The thick soup thus puts more of the can’s original gravitational potential energy into rotation than the thin soup, and the can rolls more slowly, as seen in [link] .

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics' conversation and receive update notifications?