| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

The information presented in this section supports the following AP® learning objectives and science practices:

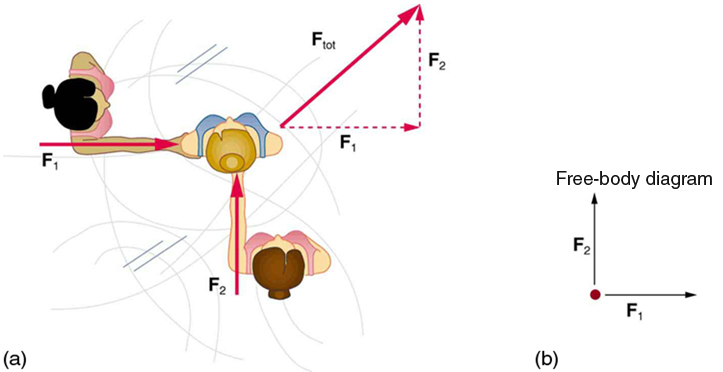

Dynamics is the study of the forces that cause objects and systems to move. To understand this, we need a working definition of force. Our intuitive definition of force —that is, a push or a pull—is a good place to start. We know that a push or pull has both magnitude and direction (therefore, it is a vector quantity) and can vary considerably in each regard. For example, a cannon exerts a strong force on a cannonball that is launched into the air. In contrast, Earth exerts only a tiny downward pull on a flea. Our everyday experiences also give us a good idea of how multiple forces add. If two people push in different directions on a third person, as illustrated in [link] , we might expect the total force to be in the direction shown. Since force is a vector, it adds just like other vectors, as illustrated in [link] (a) for two ice skaters. Forces, like other vectors, are represented by arrows and can be added using the familiar head-to-tail method or by trigonometric methods. These ideas were developed in Two-Dimensional Kinematics .

By definition, force is always the result of an interaction of two or more objects. No object possesses force on its own. For example, a cannon does not possess force, but it can exert force on a cannonball. Earth does not possess force on its own, but exerts force on a football or on any other massive object. The skaters in Figure 4.3 exert force on one another as they interact.

No object can exert force on itself. When you clap your hands, one hand exerts force on the other. When a train accelerates, it exerts force on the track and vice versa. A bowling ball is accelerated by the hand throwing it; once the hand is no longer in contact with the bowling ball, it is no longer accelerating the bowling ball or exerting force on it. The ball continues moving forward due to inertia.

[link] (b) is our first example of a free-body diagram , which is a technique used to illustrate all the external forces acting on a body. The body is represented by a single isolated point (or free body), and only those forces acting on the body from the outside (external forces) are shown. (These forces are the only ones shown, because only external forces acting on the body affect its motion. We can ignore any internal forces within the body.) Free-body diagrams are very useful in analyzing forces acting on a system and are employed extensively in the study and application of Newton’s laws of motion.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'College physics for ap® courses' conversation and receive update notifications?