| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

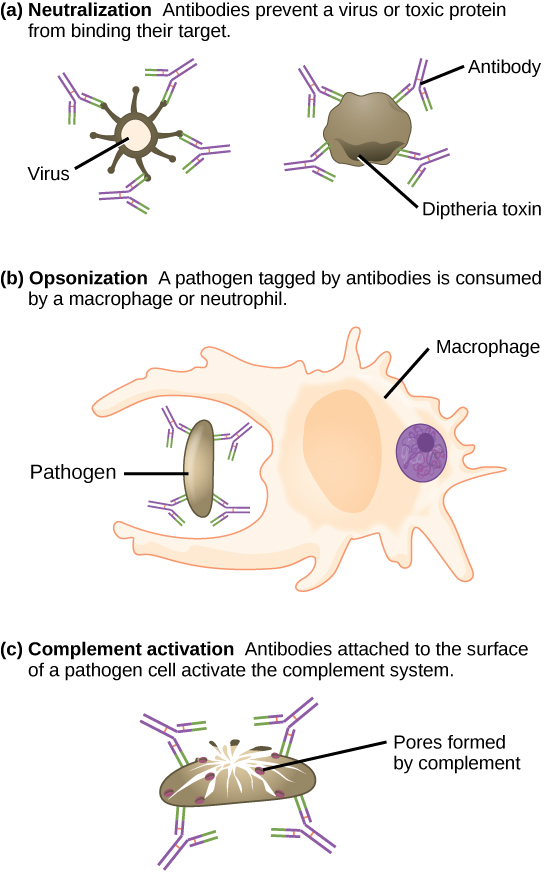

Antibodies coat extracellular pathogens and neutralize them by blocking key sites on the pathogen that enhance their infectivity (such as receptors that “dock” pathogens on host cells) ( [link] ). Antibody neutralization can prevent pathogens from entering and infecting host cells. The neutralized antibody-coated pathogens can then be filtered by the spleen and destroyed.

Antibodies also mark pathogens for destruction by phagocytic cells, such as macrophages or neutrophils, in a process called opsonization. In a process called complement fixation, some antibodies provide a place for complement proteins to bind. The combination of antibodies and complement promotes rapid clearing of pathogens.

The production of antibodies by plasma cells in response to an antigen is called active immunity and describes the host’s active immune response to an infection or to a vaccination. There is also a passive immune response where antibodies come from an outside source, instead of the individual’s own plasma cells, and are introduced into the host. For example, antibodies circulating in a pregnant woman’s body move across the placenta into the developing fetus. The child benefits from the presence of these antibodies for up to several months after birth. In addition, a passive immune response is possible by injecting antibodies into an individual in the form of an antivenom to a snake-bite toxin or antibodies in blood serum to help fight a hepatitis infection. This gives immediate protection since the body does not need the time required to mount its own response.

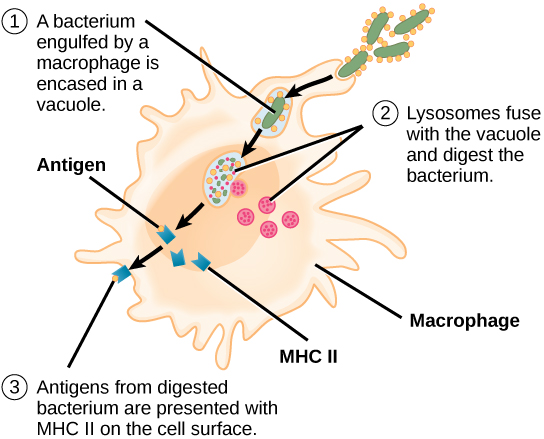

Unlike B cells, T lymphocytes are unable to recognize pathogens without assistance. Instead, dendritic cells and macrophages first engulf and digest pathogens into hundreds or thousands of antigens. Then, an antigen-presenting cell (APC) detects, engulfs, and informs the adaptive immune response about an infection. When a pathogen is detected, these APCs will engulf and break it down through phagocytosis. Antigen fragments will then be transported to the surface of the APC, where they will serve as an indicator to other immune cells. A dendritic cell is an immune cell that mops up antigenic materials in its surroundings and presents them on its surface. Dendritic cells are located in the skin, the linings of the nose, lungs, stomach, and intestines. These positions are ideal locations to encounter invading pathogens. Once they are activated by pathogens and mature to become APCs they migrate to the spleen or a lymph node. Macrophages also function as APCs. In all cases the foreign antigen is digested inside the cell, and fragments of the antigen are then displayed on the surface of the APC.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Principles of biology' conversation and receive update notifications?