| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

The United States began mired in debt. In 1789, when Hamilton took up his post, the federal debt was over $53 million. The states had a combined debt of around $25 million, and the United States had been unable to pay its debts in the 1780s and was therefore considered a credit risk by European countries. Hamilton wrote three reports offering solutions to the economic crisis brought on by these problems. The first addressed public credit, the second addressed banking, and the third addressed raising revenue.

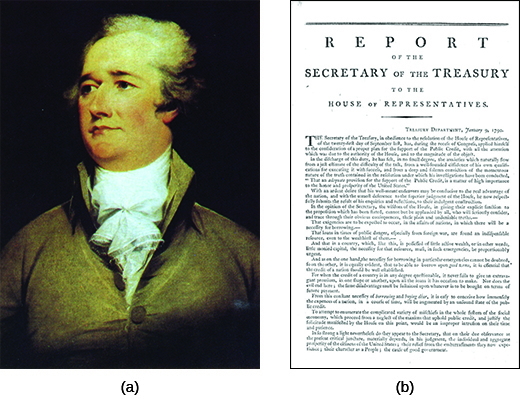

For the national government to be effective, Hamilton deemed it essential to have the support of those to whom it owed money: the wealthy, domestic creditor class as well as foreign creditors. In January 1790, he delivered his “ Report on Public Credit “ ( [link] ), addressing the pressing need of the new republic to become creditworthy. He recommended that the new federal government honor all its debts, including all paper money issued by the Confederation and the states during the war, at face value. Hamilton especially wanted wealthy American creditors who held large amounts of paper money to be invested, literally, in the future and welfare of the new national government. He also understood the importance of making the new United States financially stable for creditors abroad. To pay these debts, Hamilton proposed that the federal government sell bonds—federal interest-bearing notes—to the public. These bonds would have the backing of the government and yield interest payments. Creditors could exchange their old notes for the new government bonds. Hamilton wanted to give the paper money that states had issued during the war the same status as government bonds; these federal notes would begin to yield interest payments in 1792.

Hamilton designed his “Report on Public Credit” (later called “First Report on Public Credit”) to ensure the survival of the new and shaky American republic. He knew the importance of making the United States financially reliable, secure, and strong, and his plan provided a blueprint to achieve that goal. He argued that his plan would satisfy creditors, citing the goal of “doing justice to the creditors of the nation.” At the same time, the plan would work “to promote the increasing respectability of the American name; to answer the calls for justice; to restore landed property to its due value; to furnish new resources both to agriculture and commerce; to cement more closely the union of the states; to add to their security against foreign attack; to establish public order on the basis of upright and liberal policy.”

Hamilton’s program ignited a heated debate in Congress. A great many of both Confederation and state notes had found their way into the hands of speculators, who had bought them from hard-pressed veterans in the 1780s and paid a fraction of their face value in anticipation of redeeming them at full value at a later date. Because these speculators held so many notes, many in Congress objected that Hamilton’s plan would benefit them at the expense of the original note-holders. One of those who opposed Hamilton’s 1790 report was James Madison, who questioned the fairness of a plan that seemed to cheat poor soldiers.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?