| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Although hungry for revenge, the Texas forces under Sam Houston nevertheless withdrew across Texas, gathering recruits as they went. Coming upon Santa Anna’s encampment on the banks of San Jacinto River on April 21, 1836, they waited as the Mexican troops settled for an afternoon nap. Assured by Houston that “Victory is certain!” and told to “Trust in God and fear not!” the seven hundred men descended on a sleeping force nearly twice their number with cries of “Remember the Alamo!” Within fifteen minutes the Battle of San Jacinto was over. Approximately half the Mexican troops were killed, and the survivors, including Santa Anna, taken prisoner.

Santa Anna grudgingly signed a peace treaty and was sent to Washington, where he met with President Andrew Jackson and, under pressure, agreed to recognize an independent Texas with the Rio Grande River as its southwestern border. By the time the agreement had been signed, however, Santa Anna had been removed from power in Mexico. For that reason, the Mexican Congress refused to be bound by Santa Anna’s promises and continued to insist that the renegade territory still belonged to Mexico.

Visit the official Alamo website to learn more about the battle of the Alamo and take a virtual tour of the old mission.

In September 1836, military hero Sam Houston was elected president of Texas, and, following the relentless logic of U.S. expansion, Texans voted in favor of annexation to the United States. This had been the dream of many settlers in Texas all along. They wanted to expand the United States west and saw Texas as the next logical step. Slaveholders there, such as Sam Houston, William B. Travis and James Bowie (the latter two of whom died at the Alamo), believed too in the destiny of slavery. Mindful of the vicious debates over Missouri that had led to talk of disunion and war, American politicians were reluctant to annex Texas or, indeed, even to recognize it as a sovereign nation. Annexation would almost certainly mean war with Mexico, and the admission of a state with a large slave population, though permissible under the Missouri Compromise, would bring the issue of slavery once again to the fore. Texas had no choice but to organize itself as the independent Lone Star Republic. To protect itself from Mexican attempts to reclaim it, Texas sought and received recognition from France, Great Britain, Belgium, and the Netherlands. The United States did not officially recognize Texas as an independent nation until March 1837, nearly a year after the final victory over the Mexican army at San Jacinto.

Uncertainty about its future did not discourage Americans committed to expansion, especially slaveholders, from rushing to settle in the Lone Star Republic, however. Between 1836 and 1846, its population nearly tripled. By 1840, nearly twelve thousand enslaved Africans had been brought to Texas by American slaveholders. Many new settlers had suffered financial losses in the severe financial depression of 1837 and hoped for a new start in the new nation. According to folklore, across the United States, homes and farms were deserted overnight, and curious neighbors found notes reading only “GTT” (“Gone to Texas”). Many Europeans, especially Germans, also immigrated to Texas during this period.

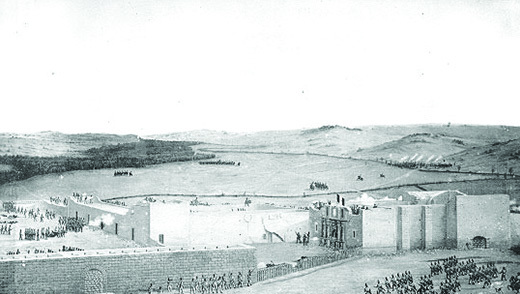

In keeping with the program of ethnic cleansing and white racial domination, as illustrated by the image at the beginning of this chapter, Americans in Texas generally treated both Tejano and Indian residents with utter contempt, eager to displace and dispossess them. Anglo-American leaders failed to return the support their Tejano neighbors had extended during the rebellion and repaid them by seizing their lands. In 1839, the republic’s militia attempted to drive out the Cherokee and Comanche.

The impulse to expand did not lay dormant, and Anglo-American settlers and leaders in the newly formed Texas republic soon cast their gaze on the Mexican province of New Mexico as well. Repeating the tactics of earlier filibusters, a Texas force set out in 1841 intent on taking Santa Fe. Its members encountered an army of New Mexicans and were taken prisoner and sent to Mexico City. On Christmas Day, 1842, Texans avenged a Mexican assault on San Antonio by attacking the Mexican town of Mier. In August, another Texas army was sent to attack Santa Fe, but Mexican troops forced them to retreat. Clearly, hostilities between Texas and Mexico had not ended simply because Texas had declared its independence.

The establishment of the Lone Star Republic formed a new chapter in the history of U.S. westward expansion. In contrast to the addition of the Louisiana Territory through diplomacy with France, Americans in Texas employed violence against Mexico to achieve their goals. Orchestrated largely by slaveholders, the acquisition of Texas appeared the next logical step in creating an American empire that included slavery. Nonetheless, with the Missouri Crisis in mind, the United States refused the Texans’ request to enter the United States as a slave state in 1836. Instead, Texas formed an independent republic where slavery was legal. But American settlers there continued to press for more land. The strained relationship between expansionists in Texas and Mexico in the early 1840s hinted of things to come.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?