| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

Leukopenia is a condition in which too few leukocytes are produced. If this condition is pronounced, the individual may be unable to ward off disease. Excessive leukocyte proliferation is known as leukocytosis . Although leukocyte counts are high, the cells themselves are often nonfunctional, leaving the individual at increased risk for disease.

Leukemia is a cancer involving an abundance of leukocytes. It may involve only one specific type of leukocyte from either the myeloid line (myelocytic leukemia) or the lymphoid line (lymphocytic leukemia). In chronic leukemia, mature leukocytes accumulate and fail to die. In acute leukemia, there is an overproduction of young, immature leukocytes. In both conditions the cells do not function properly.

Lymphoma is a form of cancer in which masses of malignant T and/or B lymphocytes collect in lymph nodes, the spleen, the liver, and other tissues. As in leukemia, the malignant leukocytes do not function properly, and the patient is vulnerable to infection. Some forms of lymphoma tend to progress slowly and respond well to treatment. Others tend to progress quickly and require aggressive treatment, without which they are rapidly fatal.

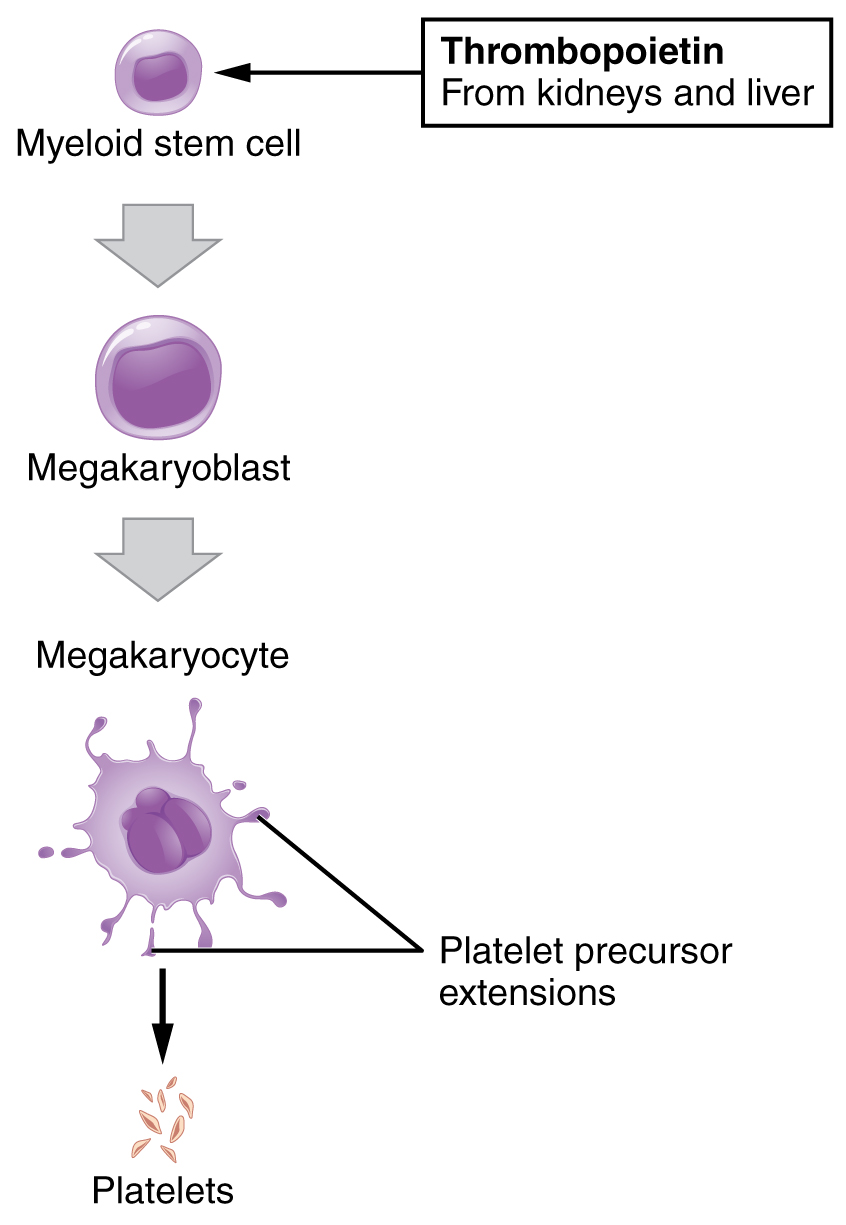

You may occasionally see platelets referred to as thrombocytes , but because this name suggests they are a type of cell, it is not accurate. A platelet is not a cell but rather a fragment of the cytoplasm of a cell called a megakaryocyte that is surrounded by a plasma membrane. Megakaryocytes are descended from myeloid stem cells (see [link] ) and are large, typically 50–100 µ m in diameter, and contain an enlarged, lobed nucleus. As noted earlier, thrombopoietin, a glycoprotein secreted by the kidneys and liver, stimulates the proliferation of megakaryoblasts, which mature into megakaryocytes. These remain within bone marrow tissue ( [link] ) and ultimately form platelet-precursor extensions that extend through the walls of bone marrow capillaries to release into the circulation thousands of cytoplasmic fragments, each enclosed by a bit of plasma membrane. These enclosed fragments are platelets. Each megakarocyte releases 2000–3000 platelets during its lifespan. Following platelet release, megakaryocyte remnants, which are little more than a cell nucleus, are consumed by macrophages.

Platelets are relatively small, 2–4 µ m in diameter, but numerous, with typically 150,000–160,000 per µ L of blood. After entering the circulation, approximately one-third migrate to the spleen for storage for later release in response to any rupture in a blood vessel. They then become activated to perform their primary function, which is to limit blood loss. Platelets remain only about 10 days, then are phagocytized by macrophages.

Platelets are critical to hemostasis, the stoppage of blood flow following damage to a vessel. They also secrete a variety of growth factors essential for growth and repair of tissue, particularly connective tissue. Infusions of concentrated platelets are now being used in some therapies to stimulate healing.

Thrombocytosis is a condition in which there are too many platelets. This may trigger formation of unwanted blood clots (thrombosis), a potentially fatal disorder. If there is an insufficient number of platelets, called thrombocytopenia , blood may not clot properly, and excessive bleeding may result.

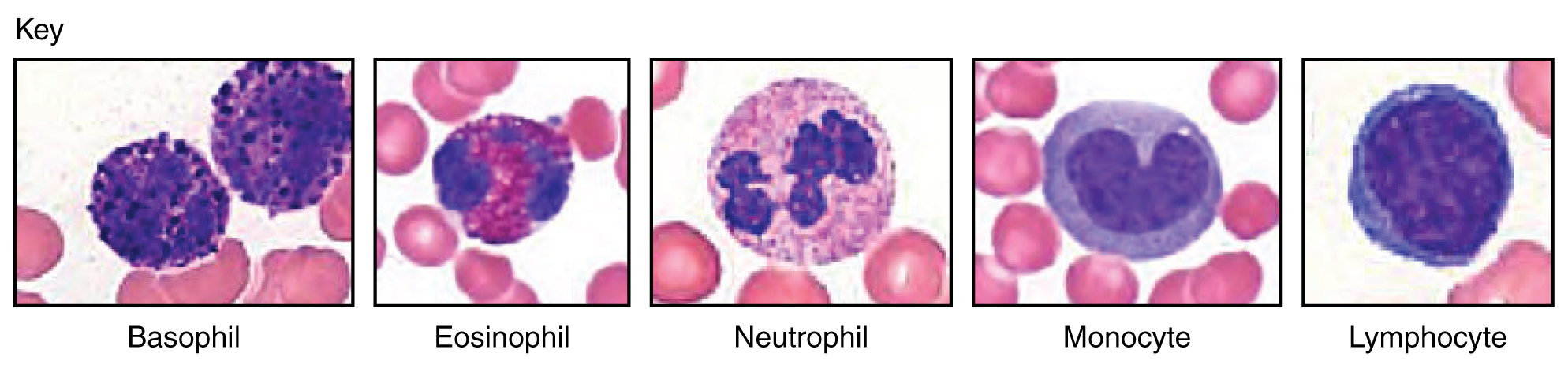

View University of Michigan Webscopes at (External Link)&cheight=733&chost=virtualslides.med.umich.edu&listview=1&title=&csis=1 and explore the blood slides in greater detail. The Webscope feature allows you to move the slides as you would with a mechanical stage. You can increase and decrease the magnification. There is a chance to review each of the leukocytes individually after you have attempted to identify them from the first two blood smears. In addition, there are a few multiple choice questions.

Are you able to recognize and identify the various formed elements? You will need to do this is a systematic manner, scanning along the image. The standard method is to use a grid, but this is not possible with this resource. Try constructing a simple table with each leukocyte type and then making a mark for each cell type you identify. Attempt to classify at least 50 and perhaps as many as 100 different cells. Based on the percentage of cells that you count, do the numbers represent a normal blood smear or does something appear to be abnormal?

Leukocytes function in body defenses. They squeeze out of the walls of blood vessels through emigration or diapedesis, then may move through tissue fluid or become attached to various organs where they fight against pathogenic organisms, diseased cells, or other threats to health. Granular leukocytes, which include neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils, originate with myeloid stem cells, as do the agranular monocytes. The other agranular leukocytes, NK cells, B cells, and T cells, arise from the lymphoid stem cell line. The most abundant leukocytes are the neutrophils, which are first responders to infections, especially with bacteria. About 20–30 percent of all leukocytes are lymphocytes, which are critical to the body’s defense against specific threats. Leukemia and lymphoma are malignancies involving leukocytes. Platelets are fragments of cells known as megakaryocytes that dwell within the bone marrow. While many platelets are stored in the spleen, others enter the circulation and are essential for hemostasis; they also produce several growth factors important for repair and healing.

[link] Are you able to recognize and identify the various formed elements? You will need to do this is a systematic manner, scanning along the image. The standard method is to use a grid, but this is not possible with this resource. Try constructing a simple table with each leukocyte type and then making a mark for each cell type you identify. Attempt to classify at least 50 and perhaps as many as 100 different cells. Based on the percentage of cells that you count, do the numbers represent a normal blood smear or does something appear to be abnormal?

[link] This should appear to be a normal blood smear.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?