| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

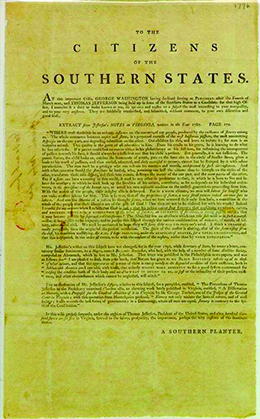

Southern planters strongly objected to Jefferson’s views on abolishing slavery and removing blacks from America. When Jefferson was a candidate for president in 1796, an anonymous “Southern Planter” wrote, “If this wild project succeeds, under the auspices of Thomas Jefferson, President of the United States, and three hundred thousand slaves are set free in Virginia, farewell to the safety, prosperity, the importance, perhaps the very existence of the Southern States” ( [link] ). Slaveholders and many other Americans protected and defended the institution.

While racial thinking permeated the new country, and slavery existed in all the new states, the ideals of the Revolution generated a movement toward the abolition of slavery. Private manumissions , by which slaveholders freed their slaves, provided one pathway from bondage. Slaveholders in Virginia freed some ten thousand slaves. In Massachusetts, the Wheatley family manumitted Phillis in 1773 when she was twenty-one. Other revolutionaries formed societies dedicated to abolishing slavery. One of the earliest efforts began in 1775 in Philadelphia, where Dr. Benjamin Rush and other Philadelphia Quakers formed what became the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Similarly, wealthy New Yorkers formed the New York Manumission Society in 1785. This society worked to educate black children and devoted funds to protect free blacks from kidnapping.

Slavery persisted in the North, however, and the example of Massachusetts highlights the complexity of the situation. The 1780 Massachusetts constitution technically freed all slaves. Nonetheless, several hundred individuals remained enslaved in the state. In the 1780s, a series of court decisions undermined slavery in Massachusetts when several slaves, citing assault by their masters, successfully sought their freedom in court. These individuals refused to be treated as slaves in the wake of the American Revolution. Despite these legal victories, about eleven hundred slaves continued to be held in the New England states in 1800. The contradictions illustrate the difference between the letter and the spirit of the laws abolishing slavery in Massachusetts. In all, over thirty-six thousand slaves remained in the North, with the highest concentrations in New Jersey and New York. New York only gradually phased out slavery, with the last slaves emancipated in the late 1820s.

The 1783 Treaty of Paris, which ended the war for independence, did not address Indians at all. All lands held by the British east of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes (except Spanish Florida) now belonged to the new American republic ( [link] ). Though the treaty remained silent on the issue, much of the territory now included in the boundaries of the United States remained under the control of native peoples. Earlier in the eighteenth century, a “middle ground” had existed between powerful native groups in the West and British and French imperial zones, a place where the various groups interacted and accommodated each other. As had happened in the French and Indian War and Pontiac’s Rebellion, the Revolutionary War turned the middle ground into a battle zone that no one group controlled.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'U.s. history' conversation and receive update notifications?