| << Chapter < Page | Chapter >> Page > |

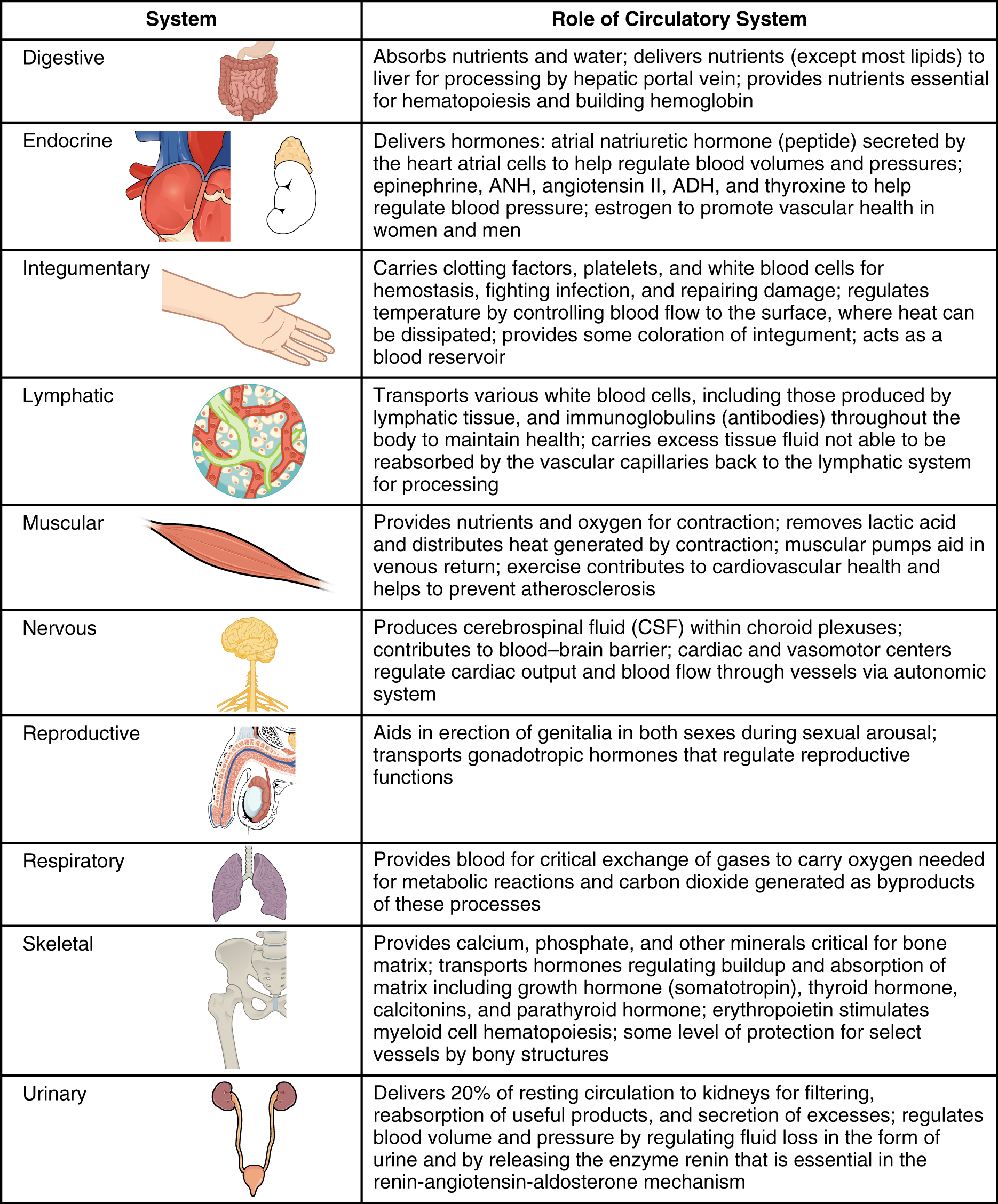

Virtually every cell, tissue, organ, and system in the body is impacted by the circulatory system. This includes the generalized and more specialized functions of transport of materials, capillary exchange, maintaining health by transporting white blood cells and various immunoglobulins (antibodies), hemostasis, regulation of body temperature, and helping to maintain acid-base balance. In addition to these shared functions, many systems enjoy a unique relationship with the circulatory system. [link] summarizes these relationships.

As you learn about the vessels of the systemic and pulmonary circuits, notice that many arteries and veins share the same names, parallel one another throughout the body, and are very similar on the right and left sides of the body. These pairs of vessels will be traced through only one side of the body. Where differences occur in branching patterns or when vessels are singular, this will be indicated. For example, you will find a pair of femoral arteries and a pair of femoral veins, with one vessel on each side of the body. In contrast, some vessels closer to the midline of the body, such as the aorta, are unique. Moreover, some superficial veins, such as the great saphenous vein in the femoral region, have no arterial counterpart. Another phenomenon that can make the study of vessels challenging is that names of vessels can change with location. Like a street that changes name as it passes through an intersection, an artery or vein can change names as it passes an anatomical landmark. For example, the left subclavian artery becomes the axillary artery as it passes through the body wall and into the axillary region, and then becomes the brachial artery as it flows from the axillary region into the upper arm (or brachium). You will also find examples of anastomoses where two blood vessels that previously branched reconnect. Anastomoses are especially common in veins, where they help maintain blood flow even when one vessel is blocked or narrowed, although there are some important ones in the arteries supplying the brain.

As you read about circular pathways, notice that there is an occasional, very large artery referred to as a trunk , a term indicating that the vessel gives rise to several smaller arteries. For example, the celiac trunk gives rise to the left gastric, common hepatic, and splenic arteries.

As you study this section, imagine you are on a “Voyage of Discovery” similar to Lewis and Clark’s expedition in 1804–1806, which followed rivers and streams through unfamiliar territory, seeking a water route from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. You might envision being inside a miniature boat, exploring the various branches of the circulatory system. This simple approach has proven effective for many students in mastering these major circulatory patterns. Another approach that works well for many students is to create simple line drawings similar to the ones provided, labeling each of the major vessels. It is beyond the scope of this text to name every vessel in the body. However, we will attempt to discuss the major pathways for blood and acquaint you with the major named arteries and veins in the body. Also, please keep in mind that individual variations in circulation patterns are not uncommon.

Notification Switch

Would you like to follow the 'Anatomy & Physiology' conversation and receive update notifications?